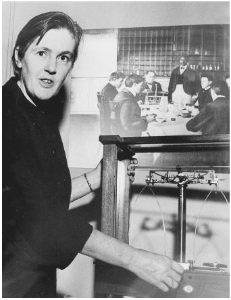

More than 50 years ago, a Canadian doctor stood in the Rose Garden at the White House as President John F. Kennedy draped a medal around her neck. Frances Oldham Kelsey was being celebrated as an exemplar of public duty for refusing to approve the drug thalidomide in the United States.

Dr. Kelsey was 48 years old then. Today, she’s on the eve of turning 101. But after a half-century wait, the B.C.-born centenarian is finally getting the tribute that had always eluded her: a national honour in the country of her birth.

In an appointment announced by Rideau Hall on Wednesday, Dr. Kelsey is being named to the Order of Canada – a poignant and significant nod to a figure who stood uniquely apart as a heroine in the midst of a public-health calamity.

“It’s nice to be remembered for something that happened so many years ago, and it’s nice no matter when,” she said from her daughter’s home in London, Ont., where Dr. Kelsey moved last fall from Washington, D.C. “It’s wonderful.”

The honour comes as Canada finally addresses its thalidomide tragedy at home. This year, Ottawa announced details of annual pensions for nearly 100 Canadians who were born in the early 1960s with severe deformities, such as flipper-like arms, because their mothers took the federally approved drug for morning sickness when they were pregnant.

As disaster unfolded in Canada, the United States took a different path, thanks in large part to Dr. Kelsey. She was a newly minted medical officer at the Food and Drug Administration in Washington when the thalidomide application came across her desk. It was expected to be a straightforward approval for a drug that was already a popular sleeping pill in Europe.

Instead, Dr. Kelsey refused to give her blessing due to concerns over health risks, and ended up shielding countless U.S. families from the drug’s devastation. She was given a distinguished service decoration and became an eminent symbol of vigilance and professionalism.

Yet she remained largely unknown in Canada, the country where she was raised and educated until she left in the 1930s after graduating from McGill University in Montreal. Dr. Kelsey had a high school named after her on her native Vancouver Island, but the nation as a whole had not paid her homage, until now.

Rideau Hall says it was honouring Dr. Kelsey for her efforts to protect public health “notably by helping to end the use of thalidomide” and for her contributions to tightening regulations for clinical drug trials.

The timing of the announcement shows that Canada is finally ready to celebrate one of its own, even if the recognition holds a mirror up to its own failings. For years, Canada tried to ignore its thalidomide fiasco. The Thalidomide Victims Association of Canada had tried repeatedly to obtain an audience with the federal government to explain the growing physical and financial toll of thalidomide on its members, but was unsuccessful until The Globe and Mail wrote about their suffering in an exposé last fall. Since then, Ottawa announced a $180-million package including yearly financial support, and Health Minister Rona Ambrose offered the government’s “sympathy and great regret” for the “tremendous suffering and personal struggle” caused by thalidomide on victims and their families.

The settlement with victims, and now the honour for Dr. Kelsey, both help close a historic circle that began with thalidomide’s appearance decades ago. To Mercédes Benegbi, head of the victims’ group, Dr. Kelsey showed strength and courage by refusing to bend to the pressures of drug-company officials, and the tribute to Dr. Kelsey is deeply deserved.

“To us, she was always our heroine,” Ms. Benegbi said on Tuesday, “even if what she did was in another country.”